“Love is more important than what we can take in life. Everything passes,” a visibly emotional Pele told a capacity crowd at Giants Stadium ahead of his footballing farewell in 1977.

Of course, he scored. He tended to. A first-half free-kick for the Cosmos against the club of his life, Santos, was the 1,282nd of a 21-year playing career.

Pele switched jerseys at halftime to turn out one last time for Santos, the team he represented between 1956 and 1974 as he ascended to heights previously unseen in professional football. It was the stuff of fantasy; make-believe made real.

The fact he spent large chunks of his career — all of those glorious, soaring highs — doing just that made it a fitting farewell. Then as now. at the moment of his passing, much of it was all about love: the joy experienced, the adoration that was impossible to resist.

Football being referred to synonymously as ‘the beautiful game’ is a tired cliche these days. But it’s a lovely label and one we probably wouldn’t have without Pele, the other Brazilian greats of his generation and their Jogo Bonito.

MORE: 70 facts about Brazil legend Pele

Born Edson Arantes do Nascimento on October 23, 1940 in Minas Gerais, Pele was the son of Celeste Arantes and Dondinho, a footballer of modest renown who played for Fluminese and Atletico Mineiro. One of the stories behind the origins of his famous nickname is classmates mocking his pronunciation of Dondinho’s team-mate Vasco de Sao Lourenco, a goalkeeper affectionately known as Bile.

“My dream was always to equal my dad,” Pele told an eponymous Netflix documentary in 2021. “I thought he was the best player in the world.”

The family lived in poverty in Baruru, Sao Paulo, where Dondinho concluded his career playing for the local club. When his father was injured and unable to play, he did not receive a wage and Pele got a job shining shoes to help the family.

It soon became clear his ambition of surpassing Dondinho’s exploits on the field could be quickly realised and a successful trial at Santos in 1956 saw him fast-tracked to the first team, making his debut as a 15-year-old in September of that year.

The Pele so familiar from online clips replayed countless times arrived remarkably fully formed. His initially skinny frame belied explosive power, flawless balance, strength when controlling the ball in tight spaces and an unerring ability to create and destroy with either foot. He ran roughshod over domestic opponents and the national team came called.

At 17, he was called up to Vicente Feola’s squad for the 1958 World Cup in Sweden. Despite starting the tournament on the treatment table, something that would become a recurring theme in Pele’s World Cup career, he broke into the team and scored the only goal in a 1-0 quarterfinal win over Wales thanks to a beautiful piece of close control, a nimble turn and cool finish.

The ebullient youngster represented rebirth for a battered football nation. In the first half of the 20th century, Uruguay and Argentina were South America’s dominant forces. The former won their second World Cup in 1950, defeating Brazil 2-1 in front of an official attendance of 173,850 at Rio’s Maracana Stadium. It became known as the ‘Maracanazo’, a disaster in sporting terms that prompted a crisis of confidence in Brazilian football.

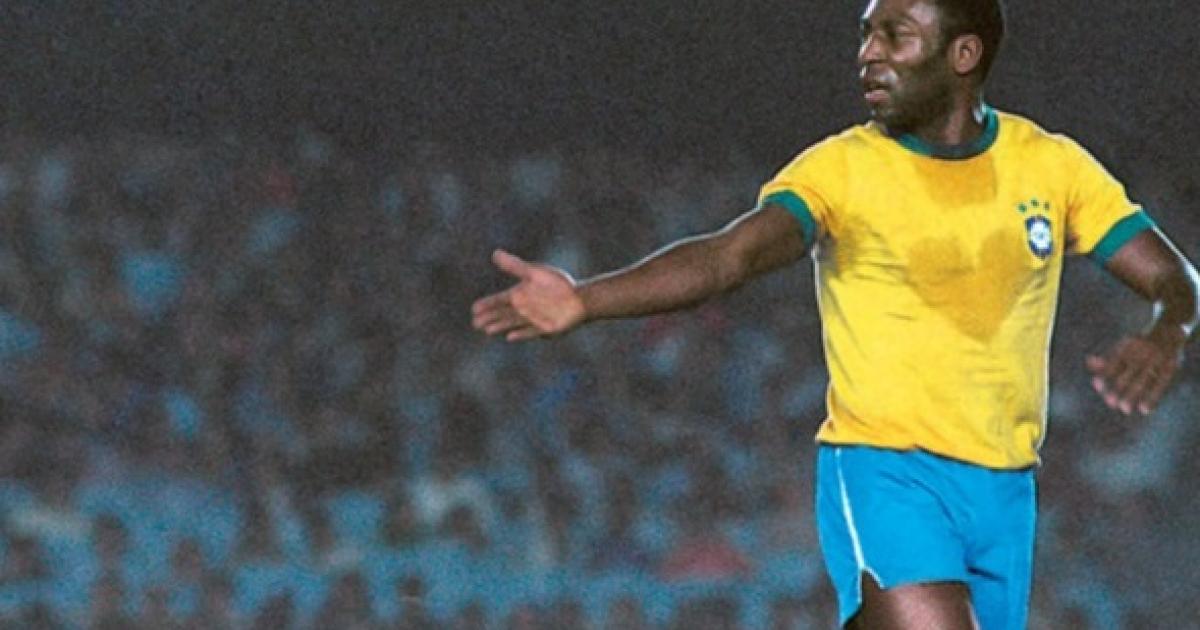

Part of this period of renewal was the switch from a white strip to the Selecao’s now iconic yellow shirts with green trim and blue shorts. With Pele as their talisman wearing that kit, they redefined what was possible in elite football as the finest international team of them all.

A hat-trick against France in the semifinal was followed by a brace against the hosts in the Stockholm final. Brazil swaggeringly won both games 5-2 and the golden boy was in tears at fulltime. Poignantly, when he rewatched the footage for the Netflix documentary more than six decades later, the tears flowed again.

They didn’t particularly seem to be ones of joy. There was a certain anguish to the sobs of an octogenarian in failing health as he observed the flickering images of his brilliant boundless younger self conquering the world. Perhaps that was the last time it felt more simple than suffocating.

A notable trait of Pele’s during that retrospective was his need for an enemy, a grudge and a score to settle. “Some journalists said that I was too young to play, that I wasn’t experienced enough,” he noted tersely regarding his stellar breakthrough involvement in Sweden, as if such a reasonable observation over an adolescent with a couple of years of senior football behind him amounted to some sort of thoughtless smear.

In this regard, it’s easy to spot parallels with another subject covered at length by the streaming giant: Michael Jordan. The ease with which the basketball great noted perceived slights and his apparent refusal to forget even the most trivial of those loaded the Last Dance documentary series with rich meme potential.

Maybe this is one of the tricks that the greatness the likes of Pele, Jordan and few others produce requires. It enables them to face down the faintest hint of complacency, to never settle, leading to perpetual success but only fleeting contentment. It means the true enjoyment may ultimately reside with those lucky enough to simply watch at the time or replay spellbinding moments over and over today.

That was Pele’s great gift to the world and he unfurled it at a time when rapid developments in travel, technology, communications and media were making the globe a smaller place. Santos were building a formidable team, and fans in Europe and beyond clamoured to see their star attraction in the flesh.

A punishing schedule of money-spinning friendlies were arranged alongside Santos’ domestic commitments and Pele thrilled against the likes of Inter Milan, Real Madrid and Barcelona. These matches are responsible for some of the mirth around Pele’s career goals record.

Out of his phenomenal haul, Santos club historian Odir Cunha told ESPN in 2021 that 448 were scored in friendlies or continental friendly tournaments. But these feats have to be viewed in the context of this time, when the European Cup and Copa Libertadores were in their infancy.

Pele’s exploits on the road for Santos did much to inspire curiosity in what might happen should the best teams from leading countries meet more frequently. The matches quickly developed a cache and were generally fiercely contested. It’s not hard to trace a line from them to the modern Champions League behemoth.

Back in South America, Santos won the third and fourth editions of the Libertadores, ending Uruguay giants Penarol’s ambitions of three in a row before prevailing amid the famed hostility of Boca Juniors’ Bombonera.

Pele scored twice as his team beat Penarol 3-0 in a deciding playoff before coming through some barbaric treatment against Boca in Buenos Aires to produce a goal and an assist in a 2-1 second-leg win, with Santos prevailing 5-3 on aggregate.

In between those successes, there was disappointment and it says something about the upward trajectory of the early years of Pele’s career that this came while winning his second World Cup.

At the 1962 tournament in Chile, he produced a sensational solo goal in Brazil’s opening 2-0 win over Mexico but an injury suffered in their next game against Czechoslovakia ruled him out of the rest of the competition, with Garrincha taking centre-stage as the Selecao won every game en route to glory.

Pele’s peripheral role that time around played a part in the clamour surrounding the world’s most famous footballer by the time 1966 in England arrived. He became the first man to score in three World Cups when he dispatched a free-kick in Brazil’s opening win against Bulgaria at Goodison Park, a match he would end injured due to roughhouse opposition tactics.

He sat out the subsequent defeat to Hungary and more punishing fouls lay in wait for a half-fit Pele as Portugal dumped the holders out at the group stage. He pledged to never play another World Cup after that bitter experience and didn’t appear in another international game of any description for two years.

This period set up an irresistible failure-redemption-glory arc in his story and, under maverick coach Joao Saldanha, Pele scored six times as Brazil won all six of their qualification games for Mexico 1970.

One of the main characteristics of great athletes is perseverance. To get ahead, you have to face adversity and not give up, even when the chance of success seems small. pic.twitter.com/YEVMSEQuQq

— Pelé (@Pele) August 8, 2022

Saldanha is representative of a part of the Pele story that has not aged especially well, namely his perceived subservience as Brazil endured a brutal military dictatorship in the mid and late 1960s.

Brazil were led in Mexico by Mario Zagallo, Pele’s teammate from the 1958 and 1962 triumphs, and not Saldanha. The coach’s bizarre comments about Pele’s eyesight coming up short in a test needlessly angered his star man, but his downfall came when he flippantly dismissed president Emilio Garrastazu Medici’s calls for prolific Atletico Mineiro striker Dario to be selected in the World Cup squad, saying Medici could insist on his favourite players being called up if he could select members of the president’s cabinet.

Saldanha’s membership of the then-illegal Brazilian Communist Party probably didn’t help matters, but given the widespread persecution and torture of dissidents in the country at that time, simply losing his job was hardly the worst outcome.

Pele’s statements at the time and subsequently were that he did not understand politics and did not wish to get involved, even though he went on to serve as Minster of Sport between 1995 and 1998 at a time when Brazil had returned to democracy. There is another Jordan parallel to be drawn from this time, considering the Chicago Bulls’ totem’s infamous “Republicans buy sneakers too” when asked to speak out in favour of progressive politics. A charitable interpretation is that Pele just wanted to get his head down and play.

Muhammad Ali and Pelé (1977) pic.twitter.com/WoqEv3FoP6

— Fight Pics That Go Hard (@fightpicsgohard) November 27, 2022

Nevertheless, the images of him smiling and waving alongside Medici after scoring his 1,000th career goal are sad in retrospect — a towering, inspirational figure reduced to a role of benign regime endorsement. Around the same time, another of his contemporaries in the pantheon, Muhammad Ali, was in boxing exile during his prime years, having refused to take part in the Vietnam War.

Pele certainly falls short next to Ali when considering how the three-time heavyweight champion inspired and championed causes beyond his sport, although it should be noted that — for all the country’s past and current flaws — the consequences Ali faced for his dissent paled next to the worst-case scenario for Pele and his family had he trodden a revolutionary path.

Ultimately, all Pele needed to inspire was a ball at his feet. That was what the revolution looked like to football fans in 1970, as the first World Cup broadcast in colour became a festival of Brazilian yellow.

The bare numbers are that Pele scored four goals, including his second in a final thanks to his towering leap to head the opener in a 4-1 win over Italy, taking his overall World Cup tally to 12 in 14 matches.

But the most celebrated moments of his finest hour arguably come when he didn’t score. The audacious near-miss from the halfway line against Czechoslovakia, the mind-bending body swerve to round the goalkeeper and drag a shot just wide against Uruguay, his peerless close control and pass to set up top scorer Jairzinho for the winner in the titanic group-stage contest against England and Gordon Banks’ implausible save to deny him in the same match.

Then there is the delicate, delicious and perfectly weighted pass to Carlos Alberto to bring the house down in the final. A feather-duster of a pass before Brazil’s skipper crammed his mallet of a right foot through the ball to conclude the greatest team goal of all time by one of the very best teams: Jairzinho, Gerson, Tostao and Rivellino all produced spellbinding play, with Pele — O Rey — the king and conductor.

Being hoisted aloft at the Azteca in Mexico City proved to be the perfect World Cup curtain call. After an unparalleled international career concluded on 92 caps and 77 goals and his Santos years wound down, a glittering final act came in the United States.

Where Pele went, the likes of Franz Beckenbauer, Johan Cruyff and George Best followed, taking part in the short-lived extravaganza that was the North American Soccer League.

It’s easy to view Pele’s three years in New York in isolation, the last and most obvious manifestation of a fantasy existence come to life as he played before celebrity-flecked packed houses at Giants Stadium. Ali, Mick Jagger, Henry Kissinger, Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand and Diane Keaton were among those in attendance for his final match.

Not long after Pele left the stage, the NASL collapsed in financial strife. But a look at soccer in the States today, with its huge youth participation, thriving MLS and era-defining women’s national team, and it is hard to imagine any of that without Pele’s transformative arrival.

He always was better when letting his football do the talking, as innumerable boilerplate interviews and lucrative commercial tie-ups demonstrated over the final decades of his life. When he was paraded around 21st-century World Cups, there was certainly an air of a man who had no inclination to even try to express anything as eloquently or fascinatingly as his magical feet once did.

It is those deeds we’re now left with, moments cherished that will not fade and are somehow enhanced by football’s modern 24-hour news and content endurathon. There was and remains so much universal love for Pele. It’s the greatest legacy for the greatest — more important than anything we can take in life.