Jerry Dipoto recalls the first time he was traded. He was a Cleveland Indians’ right-handed reliever playing winter ball in San Juan, Puerto Rico, following MLB’s strike-shortened 1994 season. He needed the innings.

It had been a trying year. Doctors discovered a cancerous tumor during a physical in spring training. He immediately had surgery in Florida to remove his thyroid gland. He beat cancer but was limited to 15 innings during the season.

To build up strength, he and a number of other major leaguers decided to play winter ball. Nov. 18, 1994, was an off day. He and several teammates spent the afternoon jet skiing, and they finished the day enjoying a few beers at a neighbor’s unit in their apartment complex. The neighbor had a TV. He didn’t. They were watching “SportsCenter” when the surreal happened: Dipoto’s mugshot showed up on the corner of the screen above the anchor’s shoulder. He was part of a six-player trade – going to the Mets, along with Paul Byrd, Dave Mlicki, and a player to be named later, for Jeromy Burnitz and Joe Roa.

From another apartment in the complex, Mike Remlinger, then a pitcher with the Mets, bolted down the hallway to find Dipoto.

“He came running down and he gave me a high-five,” Dipoto recalled during our conversation at the recent winter meetings in San Diego. “‘Bro, you’re coming to New York! We are going to be together.'”

This was before cell phones were widely available. Dipoto didn’t even have a landline in his apartment. He called his wife from a payphone in the complex’s parking lot every evening.

“It was multiple days before I was able to connect with anyone because of the lack of a phone,” Dipoto said. “The Indians, from the time they traded me – I played with the Indians organization for six years – I didn’t speak with anyone from the Indians until I encountered Dan O’Dowd when he became my GM with the Rockies five years later.

“I was thrilled because the Mets were my childhood team. A lot of my extended family still lived in that area. I had just had an emotionally difficult year, a physically difficult year. I can’t say I was pitching particularly well. I was nervous about what would happen if my strength (didn’t return). To know, in that moment, that a team thought enough of you to trade for you, that was big.”

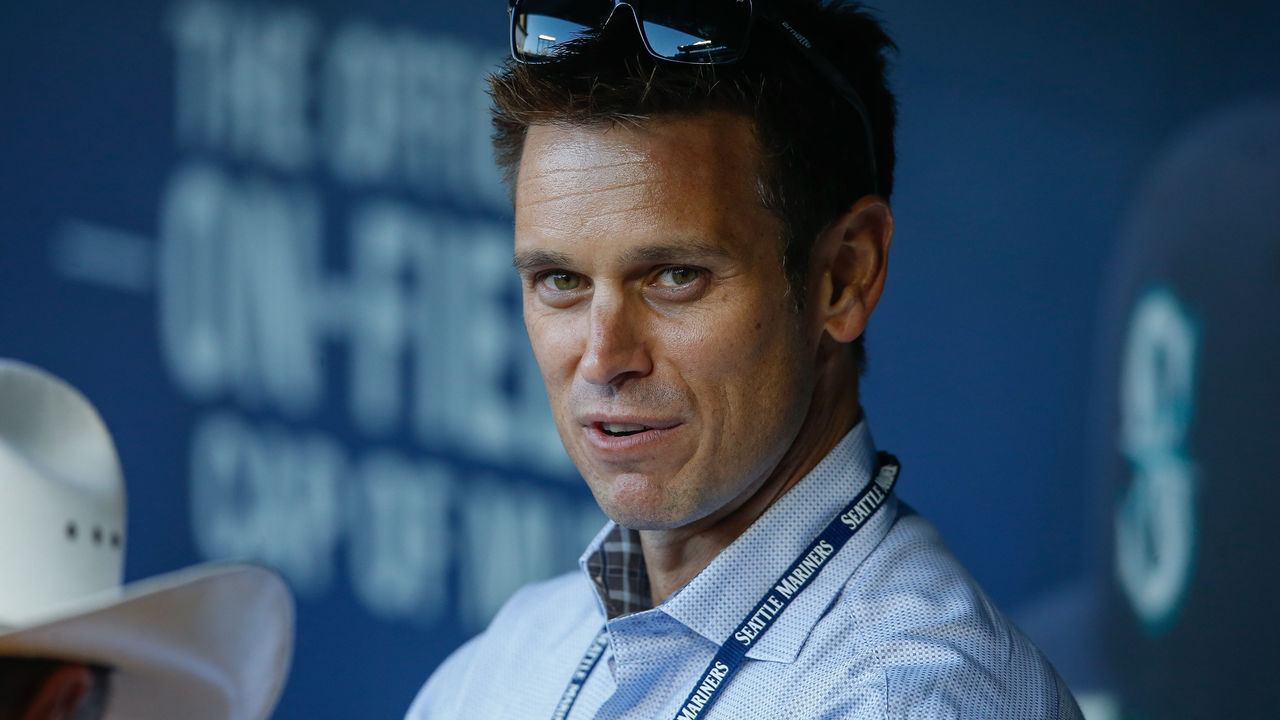

These days, as president of baseball operations for the Seattle Mariners, one of Dipoto’s great worries is communicating fast enough with players included in a trade before the news is leaked on Twitter.

Dipoto wasn’t devastated or insulted by the trade. He was excited to join the Mets. And perhaps that positive reaction is one reason why no other baseball executive has made more trades than Dipoto since he first rose to a full-time GM job with the Los Angeles Angels at the end of the 2011 season.

Since then, he’s made an MLB-high 124 trades, according to an analysis of Baseball Reference data. The next closest in that time span are Andrew Friedman (108) and Brian Cashman (107), two of the most successful executives of the century. Dipoto joined the Mariners as GM following the 2015 season and was promoted to president in 2021.

He’s averaged 11.3 trades per year since he’s become chief decision-maker. The MLB average is 7.9 a year per executive.

His 23 trades in 2017 are the most on record in a single year dating back to 1950. His 21 trades in 2016 are tied with Randy Smith (1996, Detroit Tigers) and Bing Devine (1973, St. Louis Cardinals) for the second most in a year.

“I know when I first got (to Seattle), it scared people,” Dipoto said of the trade volume. “Like, ‘Oh my God, what are we doing?’ To the point where one of the people I worked with said, ‘Isn’t that enough?'”

Dipoto countered: “I don’t know. We’re not where we need to be.”

Dipoto understands the experience of being traded and the stress that comes with moving, especially if a player has a family. He could have traded pitcher Dan Haren across the country for a slightly better return in 2010 as his first trade as an interim GM in Arizona. Instead, he honored Haren’s wish to remain out west and sent him to the Angels for a package that included Patrick Corbin, Joe Saunders, and the late Tyler Skaggs.

But Dipoto also understands the opportunity for players that comes with change, although not everyone reacts as he might.

“I’ve never called a player who we acquired in a trade and didn’t find some excitement,” Dipoto said. “Oftentimes, if the player we acquired is a veteran major-league player, he probably needed some type of change. He was playing for a team that was in the middle of a rebuild, whatever the reason, oftentimes they are excited to move to a new location.

“But more often when you pick up the phone and you call the young player, who you just traded in exchange for that guy, they are just devastated. This past summer, we made a couple of trades, and we had two of our young players ask us if they had to go. ‘Can we talk about this?’ We explained that’s not really how it worked.

“When you go through that education at a young age, there are two ways you could go. You could become jaded or bitter about the fact that it is a business. … I never took it that way as a player. The other potential outcome is you can look at it as this team thought enough of me that they are trading an All-Star-level player to get me.”

But Dipoto’s rise to become baseball’s trade king goes beyond playing experience. There are three pillars to his ability to swing a lot of deals.

Benefiting from transparency

While taking a break from his hotel suite at the winter meetings, Dipoto took in some sunlight and had an Americano on the patio of a downtown San Diego coffee shop. There he shared insights into some of the Mariners’ processes. A common theme was transparency.

Leading up to the 2022 trade deadline, Dipoto didn’t hide what the Mariners were looking for as they attempted to end the longest playoff drought in North American pro sports, which stood at 20 consecutive seasons.

“Our biggest need or our primary objective going into this deadline is to find a way to add to our rotation,” Dipoto said on July 14.

He acknowledged that there was “a tax,” a higher price, for teams acquiring high-end talent at the deadline as opposed to the offseason.

What did the Mariners do? Fifteen days later, they acquired Cincinnati Reds ace Luis Castillo, who helped Seattle reach the postseason and started a game in both playoff series. The cost was four minor-league players, three of whom were among the top five in their system.

Dipoto said later: “We did pay a premium to get him, and I’d do it again in a minute.”

He was transparent about what the club wanted and understood the price would be considerable.

And it’s this transparency that is perhaps most important to understanding Dipoto’s trade activity.

Milwaukee Brewers baseball operations president Matt Arnold made a trade with Dipoto earlier this month, sending Kolten Wong to the Mariners for Jesse Winker and Abraham Toro.

“You get a sense of where he stands on players,” Arnold said. “He’s very transparent on what he’s looking to accomplish. You don’t have to go back and say, ‘Are you sure about this?'”

Cleveland Guardians president Chris Antonetti said: “He’s looking to make a fair deal that makes sense.”

Justin Hollander, now the Mariners GM, said Dipoto’s openness is key in facilitating deals.

“As a general rule, he is probably more transparent than most – whether that is with teams, or going on the radio or TV and just saying what he thinks,” Hollander said. “For instance, he might say, ‘I think we need a right-handed hitting outfielder to serve as a platoon partner,’ rather than cryptically say, ‘We are looking for ways to get better.’ Jerry will just say this is what we think we need to round out our roster.

“Some of that transparency helps inform what we may or may not need, and what we are or are not willing to do. I worked with someone a long time ago who talked about the inefficiencies of the trade market. (He said), ‘If everyone had perfect information about what other teams’ actual needs were, there would probably be a lot more trades.’ … Someone else framed it to me like (more information) would be like the perfect organ donation system, where everyone signed up. … You would match with someone who signed up.”

Said Arnold: “Half the battle is just making sure you are in play. In order to capitalize on the market, you have to know what the market is. It takes a lot of work to stay on top of that.”

Teams generally know what the Mariners need, and what they’re willing to give up. It helps to facilitate deals, Hollander said.

“There’s no worse feeling than when you are in a front office and you see someone else has acquired a player that you love, and you think to yourself ‘Damn, I wish we would have known he was available,'” Hollander said. “Transparency hopefully minimizes those moments. Maybe it costs you something. … I’m sure there’s a trade-off out there. I’m not sure what that trade-off is.”

Dipoto’s openness comes from a confidence that his front-office team will earn his edge elsewhere. “I’ll tell you what we do. Our challenge is to do it better. That’s generally how we work.”

Eliminating fear

Dipoto pitched 12 years in pro ball, eight in the major leagues. One of the toughest things to deal with, Dipoto says, was to enter a game as a reliever, give up a game-winning hit, and return to the clubhouse. He cites those experiences as one reason he’s not fearful of a trade going south and the resulting backlash from media and fans.

“I got to pitch for 12 years, and I got to hang a ton of sliders,” Dipoto said. “And you are the one who wears the brunt of disgust. You have to walk back into the clubhouse and hold your head up high. Your teammates just worked for three hours to build this lead that you gave up. You learn how to deal with those mistakes (being) part of the game. I think making moves comes with an understanding that you’re going to make mistakes and you have to if you are going to get better.

“This is going to sound terrible, especially to the people who pay me to do my job, but you have to be willing to make a mistake.”

Andy McKay, the Mariners’ assistant general manager, noted how rare it is for someone to have Dipoto’s career path: to rise to the major leagues, and then rise to the top of baseball operations, where jobs are even fewer and teams are leaning toward hiring younger candidates with Ivy League degrees.

These days, major-league playing experience is rare among top executives. Dipoto, Chris Young of the Rangers, and Sam Fuld of the Phillies are the outliers.

Dipoto, 54, has also beaten cancer, a blood clot in 1998, and endured spinal fusion surgery that ended his playing career after the 2000 season. He completed a trade in 2018 from a Las Vegas hospital bed where he was getting treatment for another blood clot.

Said McKay of Dipoto’s willingness to deal: “I can tell you Jerry is not afraid.”

But executives say there are some among them who do pause when deciding whether or not to make a deal because they’re afraid to lose it.

While teams are trading more than in past eras, Dipoto is still an outlier.

In the 1950s, executives didn’t trade much, averaging 4.7 trades per year, according to the Baseball Reference data. In the 1960s, that increased to 5.5 trades per year per team. Trades leveled out through the next four decades: 6.8 in the 1970s; 6.1 in the 1980s; 6.4 in the 1990s; 6.7 in the 2000s.

But in the 2010s, a record level of activity was reached – 7.6 trades per executive – and it’s being maintained early in the 2020s (7.4).

Dipoto is averaging four more trades than the average executive during his tenure. On the other end of the spectrum, Cardinals president John Mozeliak has made 44 trades since 2012, averaging four per season, the fewest with 10 or more years of tenure during that period.

Arnold said teams that value players too similarly might have difficulty making deals. Some level of asymmetry is often needed in evaluation.

But Dipoto believes there ought to be more trading, in general, if the system was operating efficiently. After all, some organizations are better at developing pitchers and ought to trade from that surplus to fill other needs.

“If we keep doing things conservatively, thinking the way we’ve always thought, you’ll never distance yourself from the field,” Dipoto said. “If you think like everyone else does, you won’t create separation. You have to do something a little bit different than they do.”

Is there an advantage to making more deals? Overall, since 1950, 33% of all WAR production on major-league rosters came from players acquired via trade. Last year, 44% of the Mariners’ WAR was acquired by trade.

But what about high-volume traders versus low-volume traders?

Since 1950, there have been 498 individual team seasons in which a GM or president made at least eight trades. Five years later, 277 of those teams had a better winning percentage, about 56%. On average, teams added 17 points to their winning percentage five years after the high-volume trade season. While we can’t assign all that improvement to trades, it’s a data point of interest. In the end, it always comes down to making the right deals rather than deals for the sake of volume.

Five years after the Mariners’ record 23-trade season in 2017, the club’s winning percentage has improved from .481 to .556 last season.

Generating ideas

The ideas for trades among the Mariners’ brain trust often start on Slack. There’s a channel called #warroom, where ideas are often born and then discussed.

“We’re pretty constantly filling up the Slack channel with ideas,” Hollander said. “Either because we talked to someone (from another club) and they may be willing to do something, or just because Jerry or myself walked 10 feet in one direction and sat down on the chair or couch and said ‘Would you?’

“Sometimes the answer is, ‘No, I wouldn’t do that. That’s terrible,’ and we laugh about it. Sometimes the answer is, ‘Maybe. Let’s talk about it with the group and see what everyone else thinks.'”

Dipoto and Hollander also try to make sure junior lieutenants feel empowered to have a voice.

A good trade idea can filter up from the general baseball operations Slack channel to the war-room channel, where a smaller number of department heads collaborate. Hollander’s office is also a regular collection area where analysts often cram in and pull up a chair to exchange ideas.

During the final day leading into the trade deadline, the Mariners held what Dipoto described as “an open Zoom room” for 18 consecutive hours, “where we were going through the names and coming up with ideas.” An unusual idea was generated by a younger analyst.

The Mariners were speaking with the Giants about acquiring Curt Casali to upgrade their backup catcher spot. One analyst suggested trying to get the Giants to add left-hander Matt Boyd to the deal. Boyd hadn’t pitched all year while rehabbing from flexor tendon surgery.

“One of our analysts said, ‘Hey, can we acquire (Boyd)?'” Dipoto said. “It wouldn’t have been a natural inclination to say, ‘Let’s go trade for the guy who hasn’t pitched all year,’ who does have a real salary, at a time when small incremental additions to our team could make a huge difference based on where we were.

“We were looking for more floor and certainty instead of upside potential, but our analyst looked at it in a different way: ‘Hey, let’s shoot for what it could be because in this case.’ … That wasn’t the direction we were looking, initially, but ultimately we acquired Matt.”

Boyd was able to get healthy and posted a 1.35 ERA with the Mariners in 14 innings down the stretch.

Rival executives said part of Dipoto’s hefty trade volume can be explained by his willingness to discuss a wide variety of trade ideas.

“He is incredibly creative,” Antonetti said. “He’s not afraid to generate ideas and bounce ideas back and forth. He’s great at problem-solving and identifying needs and interests.”

Transparency, suppressing fear, and being open to ideas have made Dipoto the greatest trader in the game. They’ve played a role in getting the Mariners back to the postseason. And until more follow his example, perhaps that gives him an edge in the marketplace.

Travis Sawchik is theScore’s senior baseball writer.